Cropwell Bishop Streets: — Barratt Close (13-11-20)

Imagine living in a world where a deadly disease is spread by droplets in the coughs and sneezes of infected people. One which commonly damages the lungs but can affect almost any part of the body.

And one that is responsible for killing around one seventh the population – and has continued doing so for thousands of years. And for which there is no known cure.

That was the real-world situation facing humanity 130 years ago. That disease was tuberculosis (TB), usually called consumption in those days: even today it kills over 2 million people every year.

I imagine that virtually all of you have had a BCG jab – a single injection that protects you from TB bacteria for life (although not every form of the TB bacteria). BCG vaccination of schoolchildren began in 1953 in the UK.

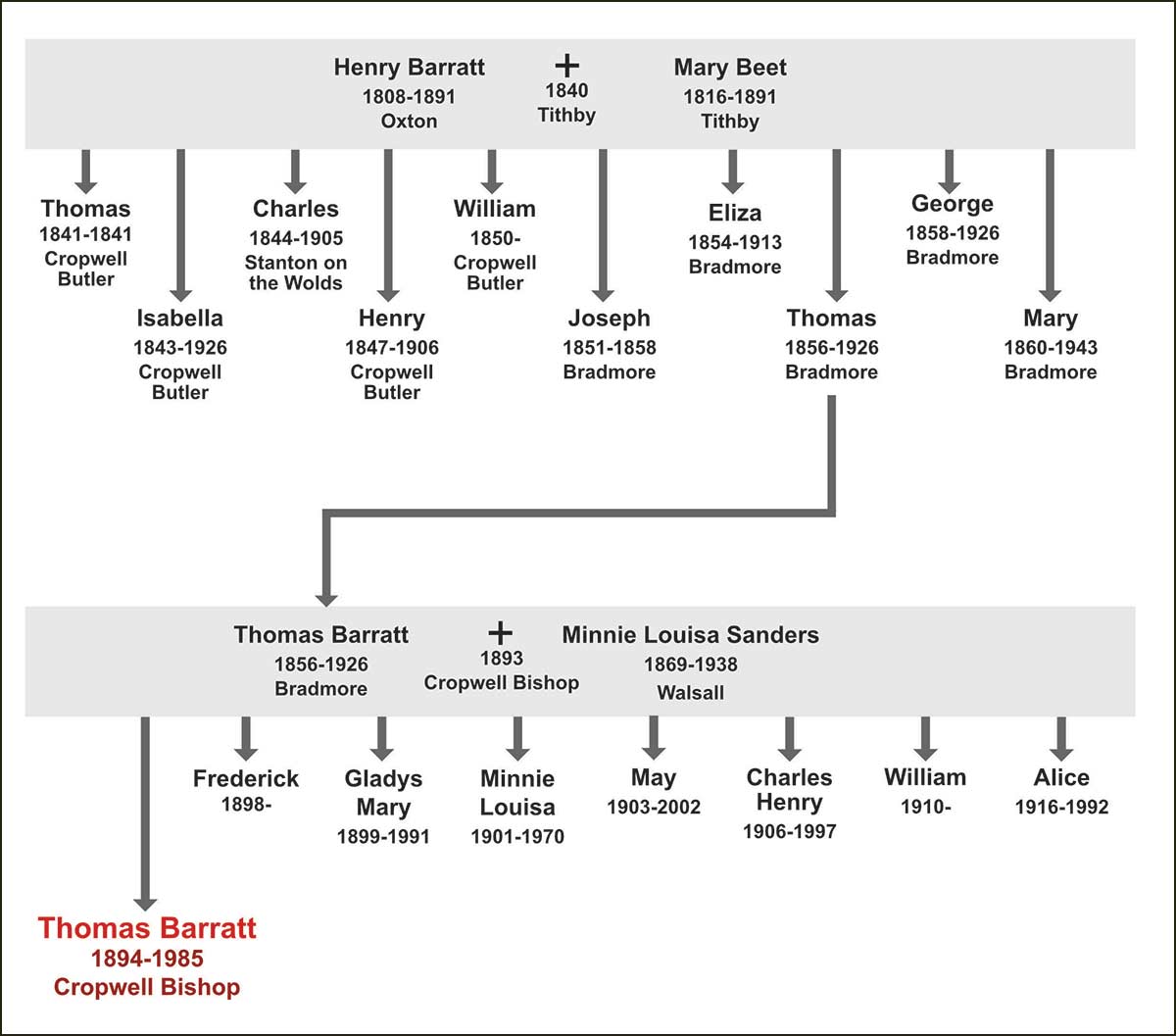

Tom Barratt was born in Cropwell Bishop in 1894. He was the first-born son of Thomas Barratt and Minnie Sanders who had married in the village the year before. Baby Tom was a healthy child – until he was 4 years old.

You need to know that, whilst most forms of TB bacteria enter a victim’s body via their lungs, there is another form of the bacteria which enters a different way – through a drink of milk.

Cows can be infected with bovine TB and it causes them to cough. Inhaling bacteria breathed out by them will infect humans too, but a much more common route is through the milk produced by the cow. However, in the 1890s this was not fully understood.

This form of TB was more likely to result in bone TB in humans and affect weight-bearing joints like the knees, hips and spine – particularly the soft bones of children.

In the 1890s, and for many decades afterwards, tens of thousands of children in the UK were infected with bovine TB every year.

Improved care during long stays in hospital kept death rates of children low, but most suffered life-changing physical damage.

When Tom Barratt was 4 years old, he became ill. In retrospect, it is clear that he contracted the human form of bovine TB as a result of drinking milk from an infected cow.

Nowadays, we know that it is easy to kill this and other harmful microbes by briefly heating milk – a process called pasteurisation after the French scientist Louis Pasteur who made this discovery in the 1880s. But in the 1890s, the link between cows and human TB was unproven.

Tom’s symptoms would have taken weeks or even months to show themselves. Limping was typically one of the first visible signs of the disease. At first, this would have been due to muscular stiffness but later, limps would become more pronounced due to shortening of the leg.

In 1908, when Tom was 14 years old, he was treated at Guys Hospital in London. At that time over 800 children a year were treated for TB at Guys. Every child’s problems were different, but the doctors decided that surgery on one knee was the best option in Tom’s case.

It is believed that this treatment shortened his leg by 7cm (3 inches). For the rest of his life he walked with a limp. A raised boot did help him cope with the problem.

This did not prevent Tom from riding a bicycle and when he was 15 years old he was working as a telegram messenger.

This probably meant him taking messages to and from the old telegraph office at Cropwell Butler. It opened in 1893 and, even in its first year, it was handling over a thousand messages a year.

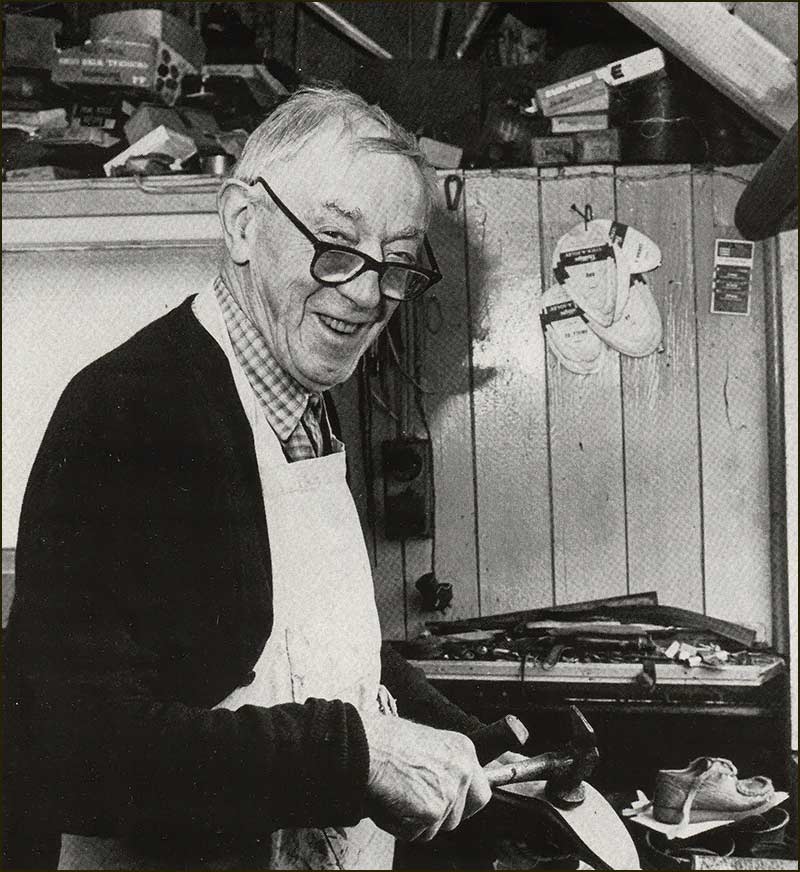

But Tom already had his sights on a very different future. A Mr Parnham was the cobbler at Whatton and Tom became his apprentice.

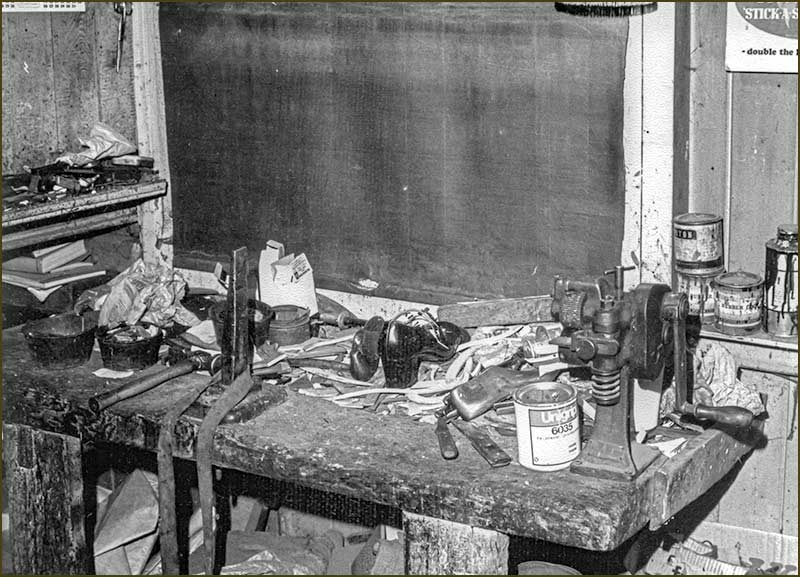

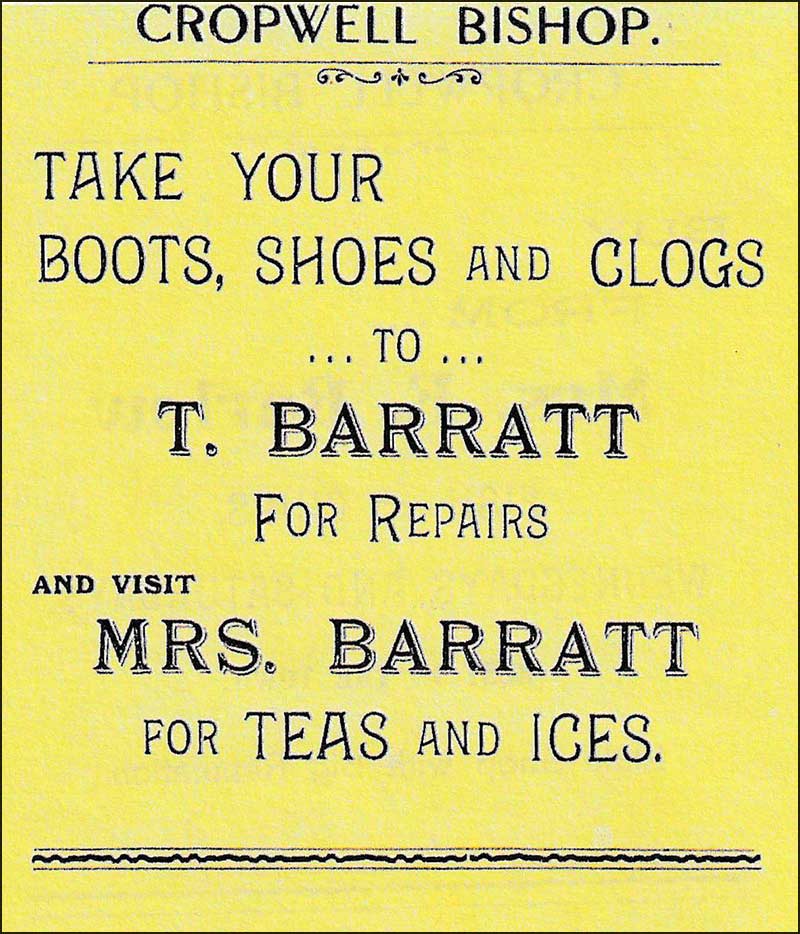

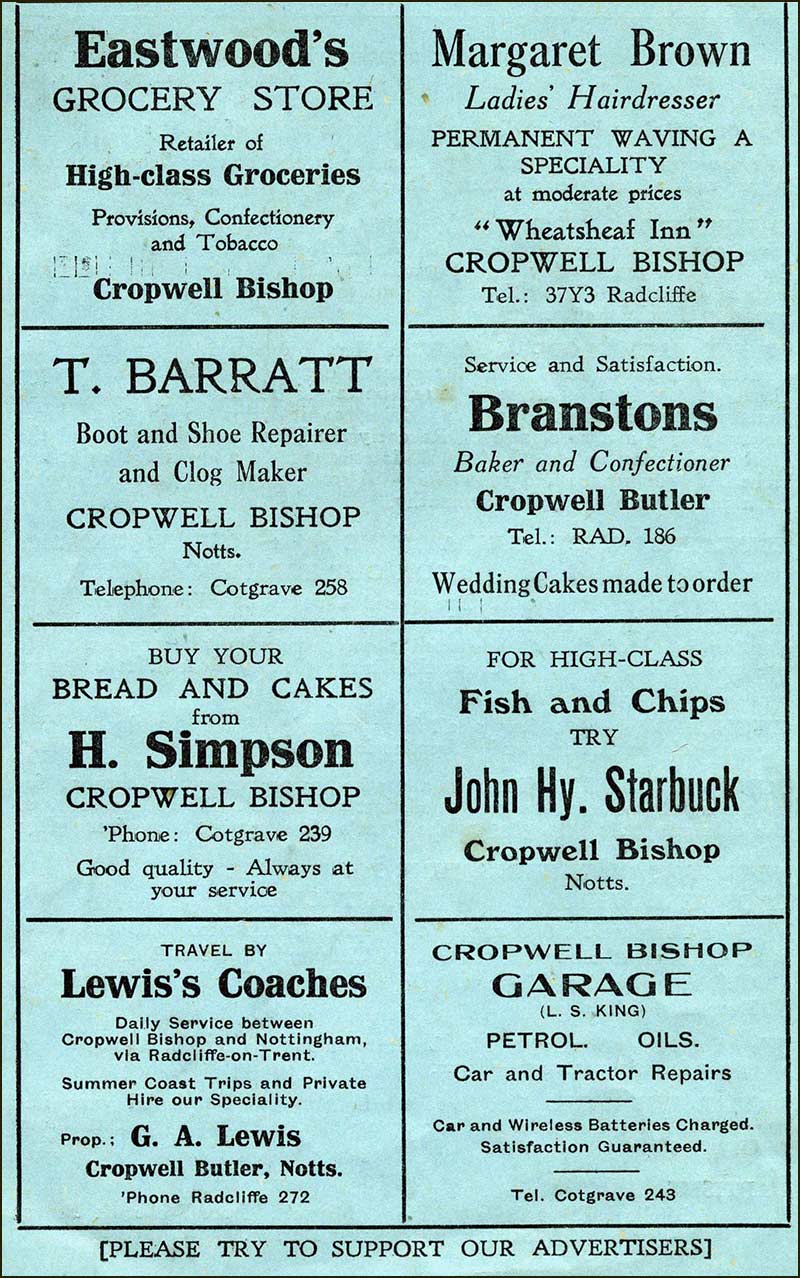

He must have been a fast learner and ambitious, because by the time he was 16 years old, he had set up his own business on Church Street. His aim was be Cropwell Bishop’s cobbler, the man to go to for the repair of boots or shoes, and the making of clogs.

For that he would need a workshop, so he bought one for £13. In fact, it was little more than a wooden shed, and he had it transported from Colston Bassett on a horse drawn dray.

The shed was to be his workshop and turned out to be an amazingly cost-effective investment. It served him for all 70 years of his business in Cropwell Bishop.

It was set up in the front garden of his parent’s house, The Rosary, on Church Street.

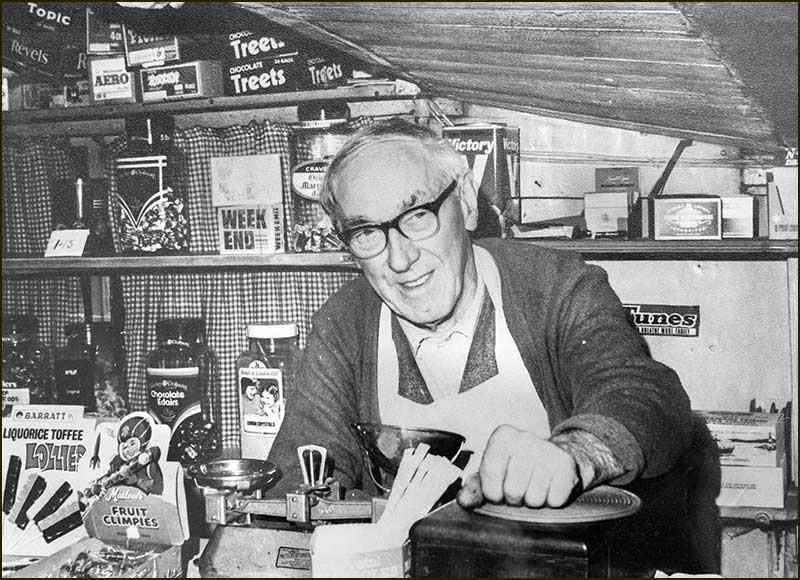

Later on, an additional shed was added and it became a shop for things other than footwear: ice creams and sweets for example, particularly for the children who were regular visitors on their way to and from school.

He used to call the little girls, “Missy”, and was still doing so 60 years later.

As a cobbler, he needed a regular supply of leather. In those days, shoes and boots had soles made of leather – and they needed repairing regularly.

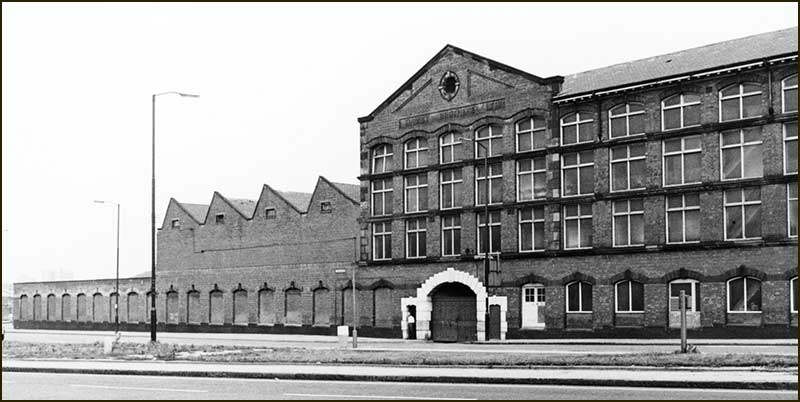

Tom could buy leather squares from Turney Brothers, Leather Works, at Trent Bridge but had to collect them himself – so, ever resourceful, he bought himself a pony and trap. He kept the pony on land behind The Rosary.

When Tom was 20 years old, he was called up to serve in the First World War, but his short leg inevitably meant that he could not take part. Whilst he could not serve the nation, he was able serve the population of Cropwell Bishop.

For much of his adult life, many villagers knew Tom by his nick-name, ‘Honky Barratt’. This had nothing to do with his limp, but all to do with ice-cream.

Tom’s mother, Minnie, made ice-cream and sold it from The Rosary.

But if there was an event taking place at the Memorial Hall or on the field, Tom would go up there on his motorbike.

He would take an ice chest, with a supply of ice-cream to sell, and would announce his arrival with a ‘honk’ of his horn: and that is how he got the nickname, “Honky Barratt”.

To make the ice-cream, Minnie needed ice, because there were no fridges or freezers in the village in those days. Her ice-cream making was only made possible by Tom fetching blocks of ice from Nottingham.

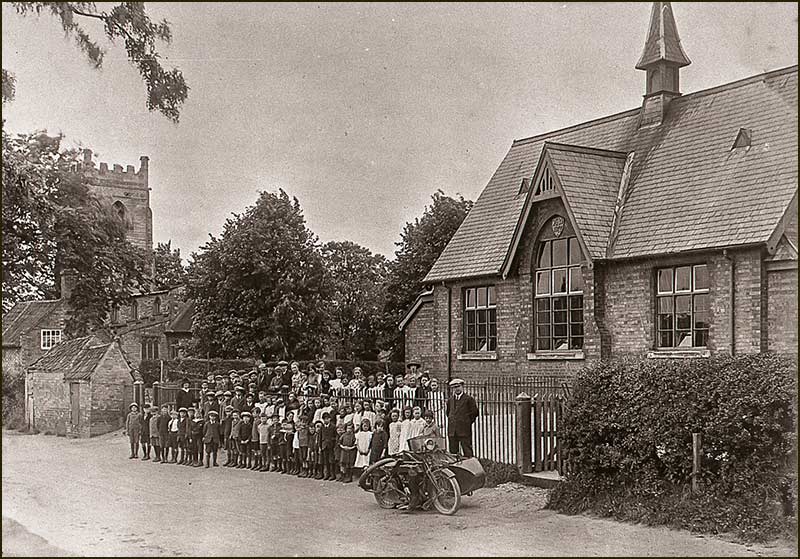

He would go on his motorbike and sidecar and buy big blocks of ice that he would carry in a chest mounted on his sidecar. We have a photograph of his motorbike. It is at the front of a photograph of schoolchildren standing outside the school on Fern Road. Tom is not in the picture.

Why his bike was there, we don’t know, but it appears to have a flat tyre so maybe it was awaiting repair. Or maybe it was to show the children, we will never know. Not even the children in the photo can tell us – unless they are 110 years old.

Few people knew it, but Tom did marry and he fathered a son. This was when he was a young man but, sadly, the marriage did not work out.

His wife came from Sheffield and, after a short, married life in Cropwell Bishop, went back there.

Even so, Tom would sometimes travel up to Sheffield to visit his son.

His career as the village cobbler was long indeed. It is sobering to think that even though he worked continuously through two World Wars, in 1945 he was still not half-way through his working life in the little workshop on Church Street.

It was during the Second World War that a bomb was offloaded on Cropwell Bishop, not far from The Rosary. No one was injured but the blast was strong enough to move a haystack. Shrapnel from it also damaged a Ford car at The Rosary, the one owned by Tom.

Having a car become important to him for his business and, in later years, for travel to the east coast.

By the 1960s he had a Rover car and used it to reach the two caravans that he then owned at Mablethorpe. He named them, The Rosary and Peter Pan, and would let them out for holidays – even transporting people to and fro in his car.

As we can see, Tom was not just the cobbler in the village; he was fully involved in village life.

You have to remember that in the years before the 1960s, everyday life took place in a social space that was tiny compared with today.

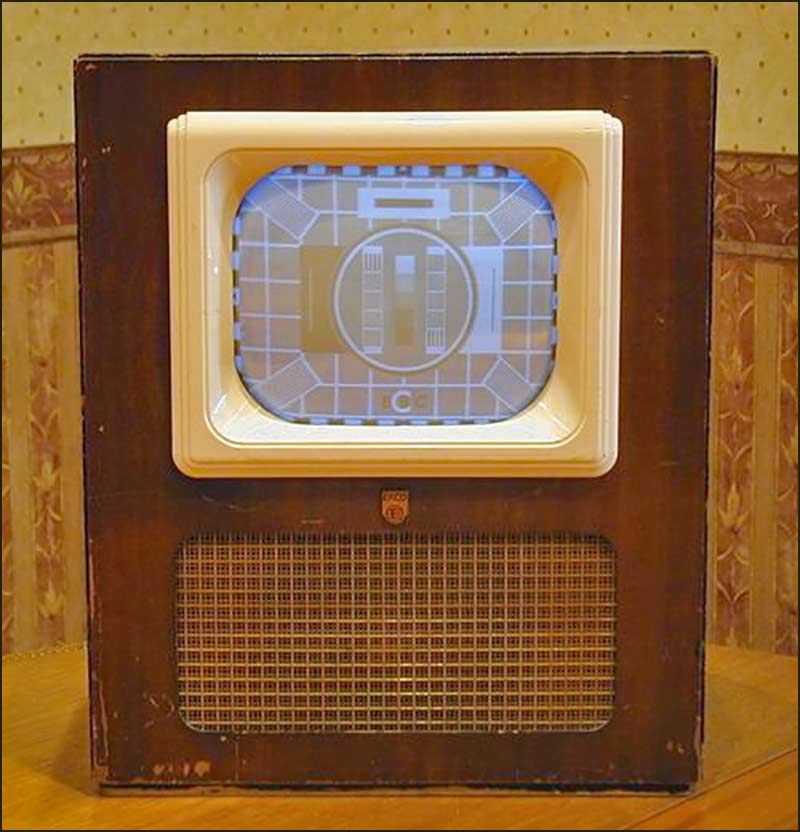

In 1953, most people watched the broadcast of the Queen’s Coronation on a friend’s TV set. This event did start a rise in the proportion of households having a TV: in 1954, 31% had one.

But it was not the TV we know of today: broadcasts were in black and white; TVs displayed just 405 lines (i.e. 405 pixels high); screens were typically 12 inches (30cm) across, and they were expensive – around £1500 in today’s money.

And you couldn’t watch a great deal. The BBC broadcast programmes for 2 hours before 1pm and none at all between 6pm & 7pm. This period was used by parents to trick children into thinking that television had finished so they would go to bed without complaint.

On Sunday, the television shown between 2pm and 4pm was intended for adults – the children were meant to be at Sunday School!

Showing 'test card' to enable you to adjust picture.

In 1955, TV viewing became more exciting: a second channel, ITV, arrived (most people called it commercial TV).

To view it, you had to buy a little box - with thick cables attached, that would sit on top of the TV.

Even the adverts were an exciting arrival with their comedy and jingles.

Also, in the 1950s, most people did not have a phone at home, they were an expensive luxury. You went to the red telephone phone box on Church Street or at the bottom of Hoe View Road to make a call. Or, if you had arranged for someone to call you, you waited outside listening for its ring.

So, life was very different. Betting on the horses, the boat-race or the FA Cup, was the limit of most people’s gambling habits – not counting the weekly shilling or two (5p or 10p) that most people spent on the Football Pools.

In Cropwell Bishop, the person you could turn to when you fancied placing a little bet, was Tom Barratt. Apparently, his shop was where you could place your bet and then, if you were lucky, collect your winnings.

In 1984, when Tom was 90 years old, he met the Queen. The meeting was at Southwell Minster when Queen Elizabeth presented Maundy money.

Each year on Maundy Thursday, which is the day before Good Friday, the Queen attends the service at a church somewhere in Britain. This particular service is then called 'Royal' Maundy and this tradition, in one form or another, has continued since the 13th Century.

The people awarded the solid silver coins are older ones from the local area. They are chosen for their service to church or community on the recommendation of local clergymen: Tom must have been thrilled to be one of those selected.

This was a crowning moment in Tom Barratt’s long and active life serving the Cropwell Bishop community.

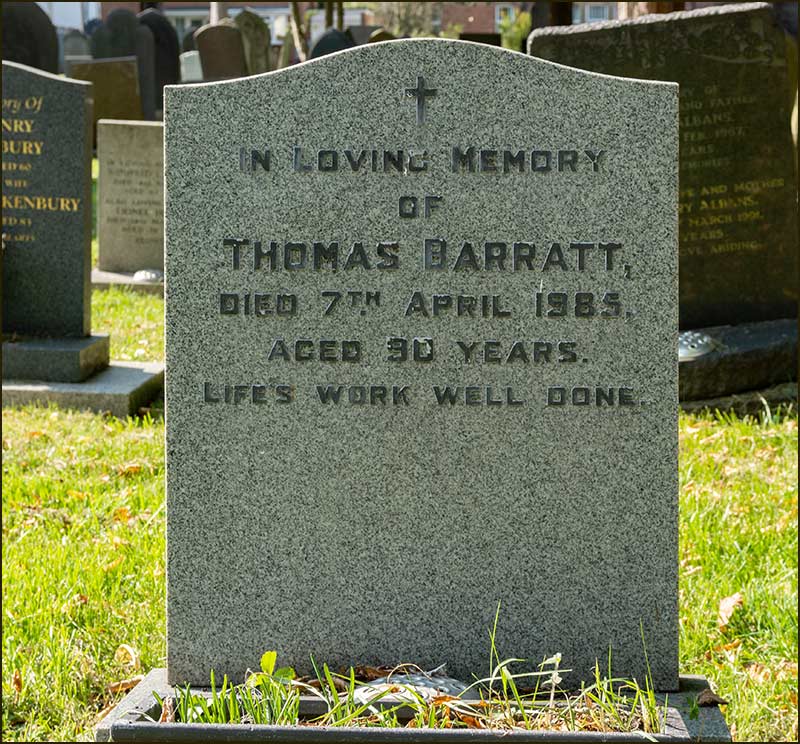

Just a year later, in April 1985, he died. He is buried in Cropwell Bishop Churchyard – only 100m from the site of The Rosary and his shop on Church Street.

Before the end of that year, plans were afoot for a small housing development off Nottingham Road.

When the homes were completed in 1987, the Parish Councillors awarded Tom Barratt another honour: they named the street Barratt Close.

From 'The Yews' to Barratt Close

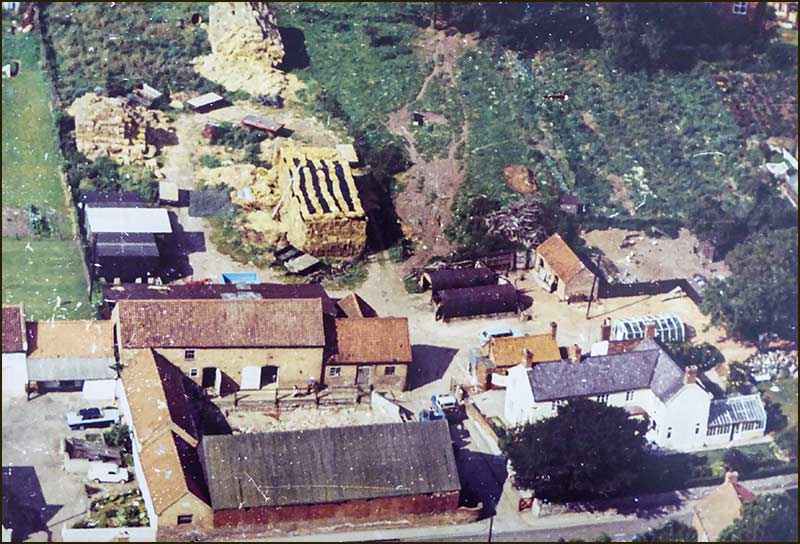

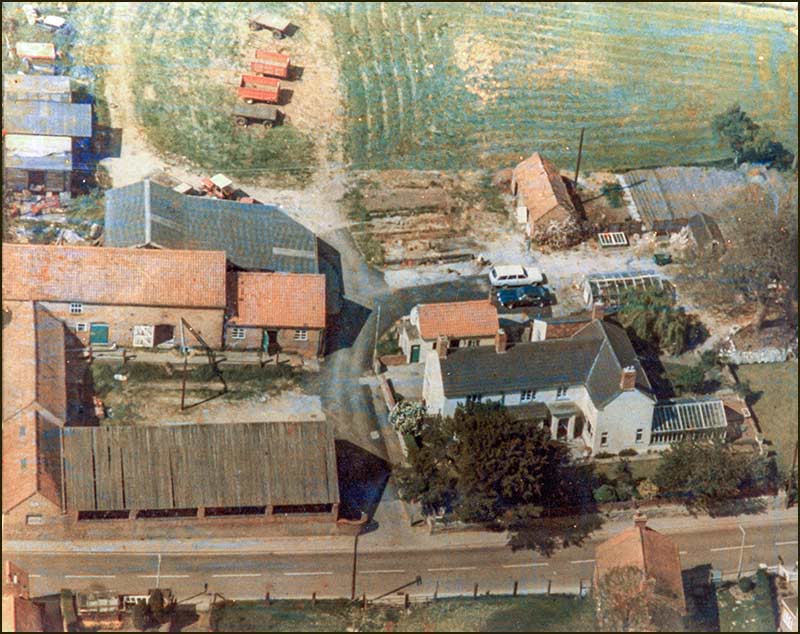

The building of homes on Barratt Close was not straight forward.

The site was an old farmyard and the plan was to covert some of the old out-buildings into two homes and then build chalet bungalows on the remaining land.

At the entrance to the Close stands the original farmhouse, The Yews. This house has since been renamed, Yew Tree House because only one yew tree remains.

The Yews faced Nottingham Road and was not part of this development, but it was linked to Barratt Close by its location and history.

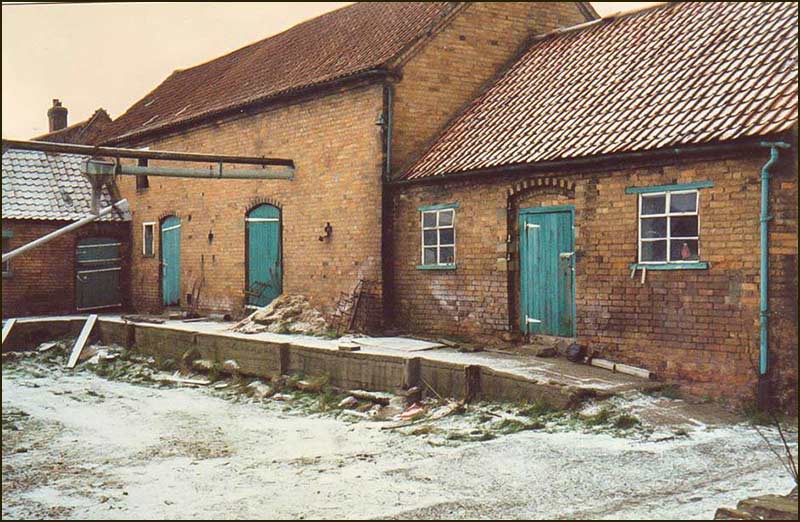

The above picture is worth a closer look.

It is possible to see through the end of the partly demolished barn, which means the end wall facing the road is no longer standing – yet the final rebuild appears almost identical.

It appears to have the same dimensions but a chimney has been added. Also, the end window has not been included and the plaque has a slightly different position.

In the centre of the picture is a small house directly across the road. It no longer stands but has been replaced by a new house during 2020, that is another wonderful example of how it is possible to erect new homes that achieve the latest building standards yet blend (even better) with surrounding properties.

In years to come, I wonder how many of the residents on Barratt Close will know the history of the site and the source of its name: will there still be a way for them to access this street story?

Tony Jarrow

Note:

Thanks to Anne Terzza, Pam Barlow, Philip Johnson (son of Tom's sister, May), John Greenwood, Anne Mansfield, Jane Jones and Stephen Reader for their help with this article.

Barratt Close in September 2020...