Cropwell Bishop Streets: — Hoe Nook (2-10-20)

I once lived on Violet Road. Nearby was Heather Road and Lavender Crescent. The housing estate was built on land that had been a garden nursery, hence the names of the roads. The council naming policy was logical, but not very imaginative.

In Cropwell Bishop the approach has been more thoughtful and interesting – even if, as I have found, it can take a bit more effort to make sense of a street name. Hoe Nook is an example. To make fully appreciate its name, we need to delve into the history of our village.

Imagine you are 20 years old and living in Cropwell Bishop in 1800. There are nearly 500 people living here in 90 houses.

You have played and walked on every patch of the parish since you could stand. You know the surrounding land by heart. Your Dad tills a strip of common land where he grows much of the potatoes and veg that your family eats. You know the names of all the fields. It has been like this for centuries.

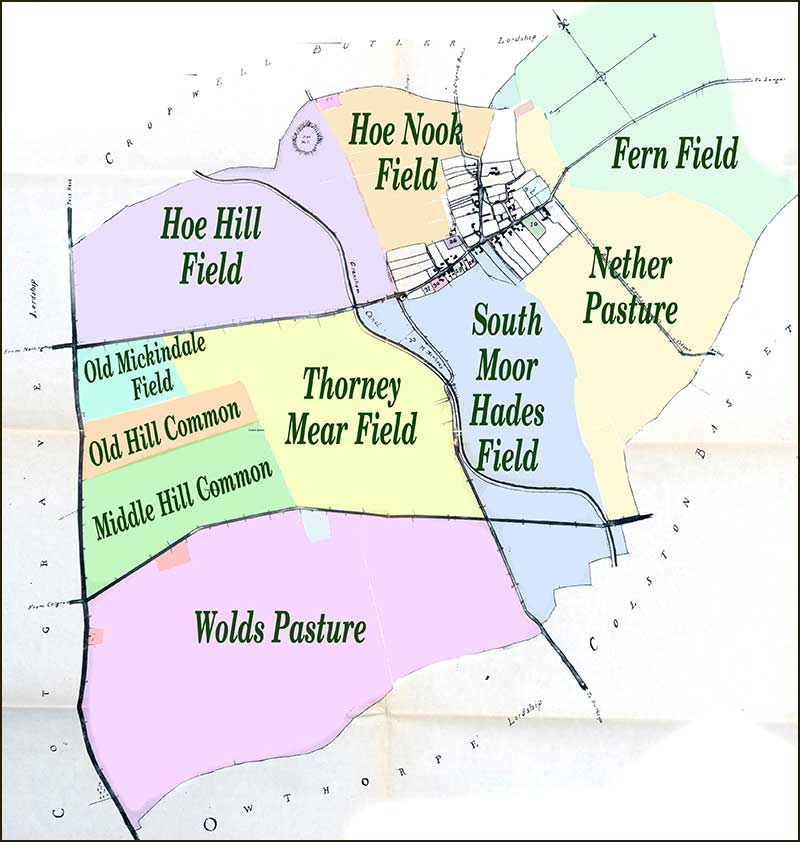

Small enclosed fields surround the centre of the village.

Then you leave the village for 5 years. Maybe you go into service at some country home or possibly join the navy. Whatever, on your return you are shocked by the changes in the village of your childhood.

The strip of land that your parents had grown food on was no longer there; one of the village farmers now owned the land along with that of your neighbours. It meant that your family could no longer grow food for themselves – they had to work full-time to earn money to buy food from shops.

It was the same for almost everyone you knew – except the bigger landowners. How could this be: what had happened while you were away?

In previous centuries, villages like Cropwell Bishop were fairly self-sufficient for the essentials in life. In fact, they had to be because transport links between populations were slow and difficult. But by 1780, the Industrial Revolution was taking off and the factory workers needed feeding.

The building of canals and better roads had improved transport links with cities and villages: Cropwell Bishop was no exception. In 1797 the Grantham Canal was completed and connected the village with both Grantham and Nottingham. The British Government decided that, like manufacturing, farming would have to change.

During the 1700s, most villages had continued the trend of enclosing fields using hedges and fences. This helped to control animal feeding and also stopped them eating other crops.

But fields were usually small, typically 1 acre, and the rate of enclosure was slow – and it was only happening where the soil was good. Surrounding marginal land went to waste.

The Government wanted to speed up the trend for enclosure and it wanted farmers to make use of the poorer land too because, if they didn't, there might not be enough food for the growing populations in the cities.

To ensure it happened, they introduced Parliamentary Enclosure Acts. These were acts of parliament which pushed villages into legally allocating ownership of all the land in its parish. In the years that followed there were over 5 thousand such Acts passed by Parliament: there was one for Cropwell Bishop in 1804.

To start the process, at least ¾ of the village had to agree to the enclosures. A farm labourer was not likely to go against a farmer’s wishes if he wanted to keep his job. As elswhere, agreement was achieved in Cropwell Bishop.

Following this agreement, a small committee came to Cropwell Bishop to hear objections. Then Parliament passed the Act in 1804 and commissioners were appointed to observe the enclosure of the land.

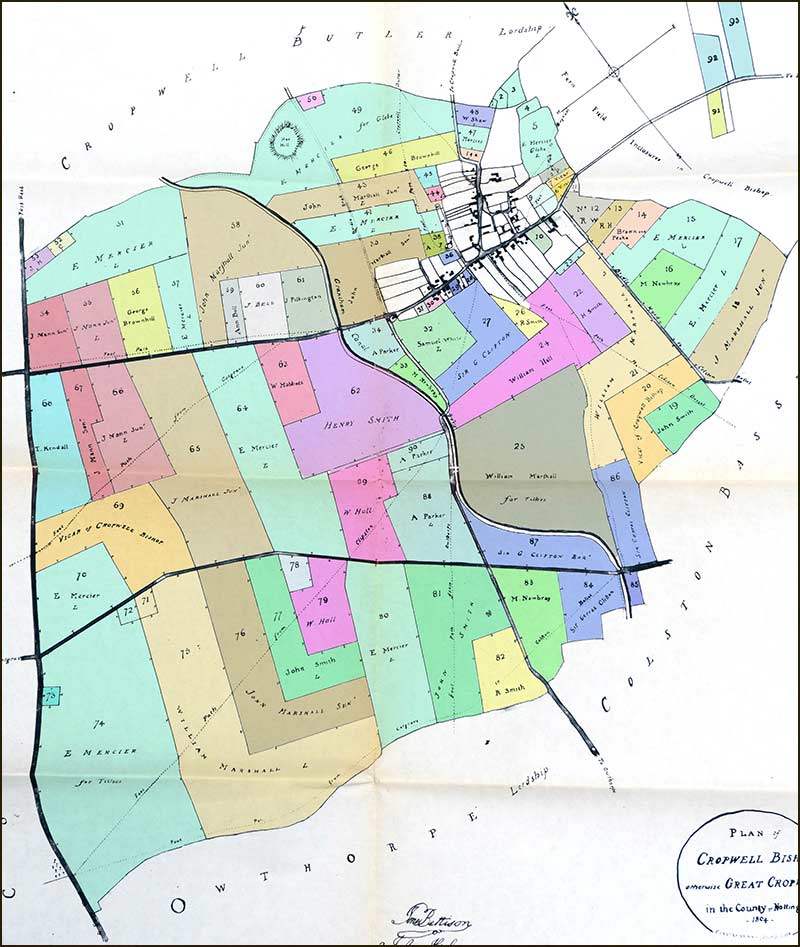

A map of existing land holdings was drawn up and landowners had to prove their legal entitlement. Then a new map was drawn giving landowners their share. These landowners then had to build fences and roads on their land. There were even regulations on how wide roads had to be.

All these changes did result in much more scrub land being cultivated. And, having cultivated fields butting up to each other, did mean the spread of weeds from waste land was much reduced. Overall, it did enable farmers to be more productive.

Generally speaking, this process proved good for the wealthy but not so good for the poor who were often deprived of making a good living.

Any land that poor people were awarded under the Act, tended to be smaller and of poorer quality, most times not having water or wood supplies (for fencing and heating).

The names of some Pre-Enclosure small owners did not appear in the Award. They were bought out by the bigger landowners, as were most of the cottagers who previously had "rights of Common" (which meant they had been entitled to use Common land in the parish to grow crops, etc).

Each colour represents a farmer/tenant.

Most field boundaries from 1804 are recognisable.

There is little doubt that the better-off farmers (particularly those who were openly supportive of the Government) did well out of the Act. They were better able to influence the commissioners who decided the location and size of fields.

It is interesting to note the many small woodlands that appeared in the farmlands of the East Midlands following the Act, variously called a spinney, holt, copse or covert. Hoe Hill is an example.

Was this because the landowners were environmentalists? Far from it, the woods were there to protect foxes and game birds – so they could later be hunted for pleasure. Fifty years ago, fox hunting was still a common sight in our parish (a young Prince Charles was once seen with the Hunt at Harby).

Sad to think that the Enclosure Act deprived poor folk of the opportunity to gather firewood, yet resulted in woods being planted to breed foxes. Bad news for poor folk but good news for foxes (sort of).

You can understand why many people opposed Enclosure Acts, but it was all to no avail.

When you compare the map of Cropwell Bishop before the Act with the one after, it is clear that there must have been a great deal of upheaval in the years after 1804.

Nevertheless, looking back from the 21st Century, such changes were inevitable; the Industrial Revolution could not be stopped and agriculture had to adapt.

Let’s return to Hoe Nook, the street.

Look again at the map of the village in 1800 and you will see that Hoe Nook Field covered the north side of the village – including the land on which Hoe Nook street now stands.

So, in naming the street, Parish Councillors were keeping alive a bit of village history. This has to be more appealing than a Violet Road or Lavender Crescent!

The bungalows and chalet-bungalows were built in around 1976 by a builder called Smedley from Hucknall. This was to be Smedley’s third build in the village: it had already built the homes on Dobbin Close and the town houses on Stockwell Lane.

At least one owner has lived on Hoe Nook since that time. Its open southernly aspect certainly has long-lasting appeal.

So, Hoe Nook is, unusually, a Cropwell Bishop street that is not named after person, but its connection with the history of our village is as strong as any other street name.

Now, we can fully appreciate that link.

Tony Jarrow

Note:

Thanks to Anne Terzza and Pam Barlow for their help with this article.

This is Hoe Nook in September 2020.