Cropwell Bishop Streets: — Kinoulton Road (20-11-20)

Kinoulton Road is so named because it leads to Kinoulton.

Whilst everyone today will see the logic in this, it is interesting to note that old writings about the village usually refer to the "Cropwell to Owthorpe Road".

Owthorpe is much closer to us than Kinoulton, especially if you take the direct route across fields, and for centuries has had close links with Cropwell Bishop — children even walked from Owthorpe to the school here in the early 1900s.

Nevertheless, whilst history might support the "Owthorpe Road" name, sign-post makers, car-drivers and Amazon-drivers are probably happier with "Kinoulton Road".

And, today, the road sign says Kinoulton Road, so that is what it is.

With that out of the way, let's examine what we know of its history over the last 230 years — starting from its northern end.

From Nottingham Road to the Canal

At the start of Kinoulton Road, there are 6 homes on the right-hand side – and they account for the majority of homes along its whole length, there being just 5 at the far end.

These homes were originally let as Council Houses and numbered 1-6, but in 1949 they became 2 to 12 Kinoulton Road.

Numbers 2 and 4 were built around 1931 and numbers 6 to 12 were built in 1944 for farm workers.

Numbers 10 and 12, were then demolished and replaced by two new detached house in 2007.

For over 10 years the race was an annual fixture in Cropwell Bishop and raised money for the Memorial Hall.

This annual event raises money for Friends of Cropwell Bishop School and Cropwell Bishop Scouts.

In 2020, COVID-19 restrictions forced the event to be a 'virtual run' that you completed alone, in your own place and time.

We all hope that in 2021, real runners will once again pound our local roads.

Here, they are celebrating its completion by all riding a final lap of the circuit. During the previous 24 hours, teams of riders took it in turn to complete a lap.

This event took place every other year during the 2000s and 2010s. It raised money for the Air Ambulance and the Memorial Hall.

It will be the second such sign they have seen because are similar signs on Colston Road and Swabs Lane.

Is this a leftover from times when houses did not exist on and around Colston Road?

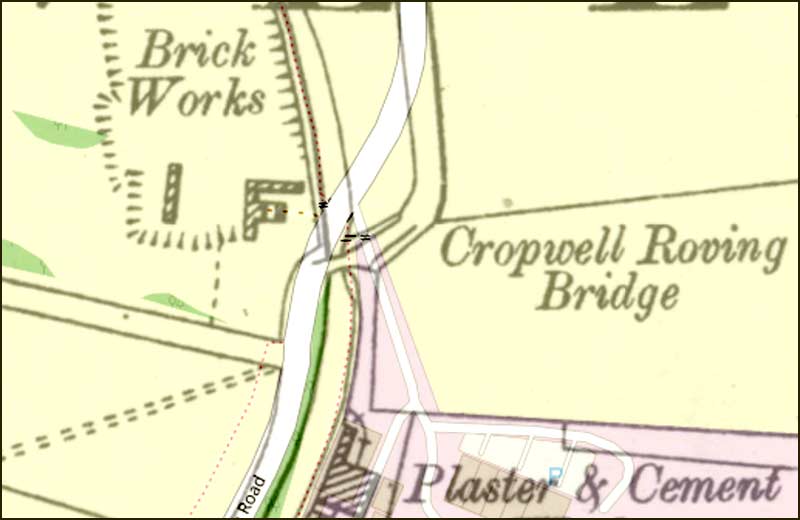

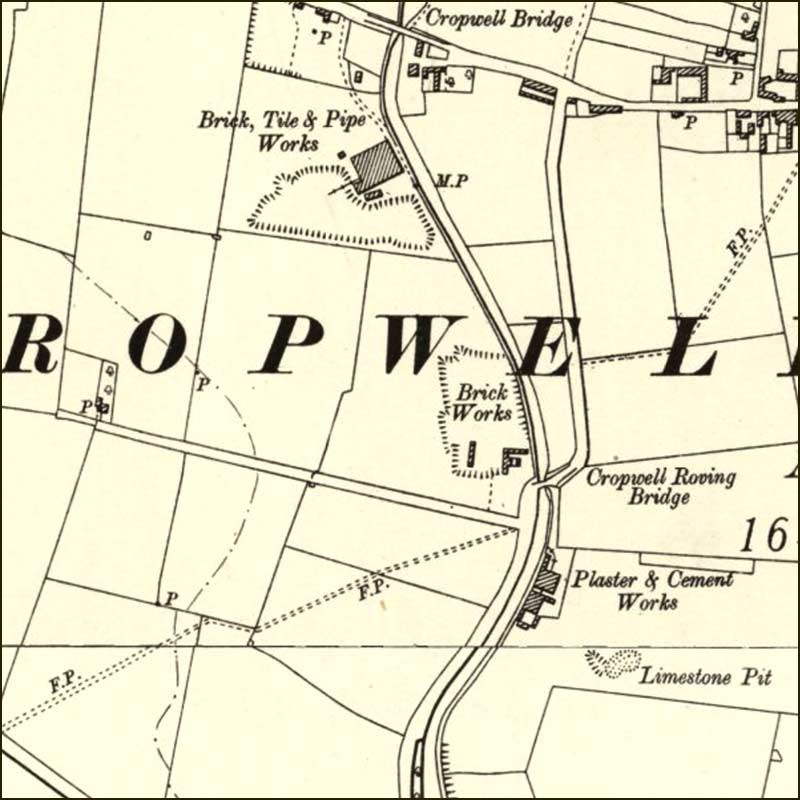

Canal Bridge 22

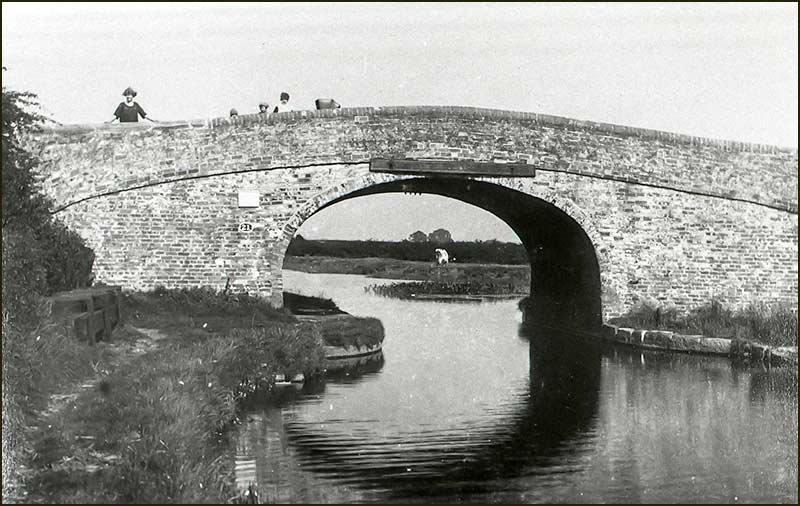

The Grantham Canal was officially abandoned in 1936 and since then, most of its bridges have been demolished and replaced with bridges that prioritise cars, not canal barges. That is why, on Kinoulton Road, Bridge 22 is now, nothing more than a painted label on a concrete lintel.

It was the only bridge over the whole length of the Grantham Canal that was a Roving Bridge. For the early barge men who used horse power, they were a blessing whenever the tow path changed from one side of the canal other — as it does here, at Bridge 22.

At the bridge, the tow path followed a route that enabled the barge men to continue their journey without even having to unhitch their horse.

There do not seem to be any surviving photographs showing how this was achieved at Bridge 22, only pictures taken from the other side. See below.

This view shows nothing out of the ordinary so the special features that made it a Roving Bridge must have been on its north side. Below is a photograph showing how it might have appeared.

A horse would have been able to cross to the path on the other side without having to be unhitched from the barge.

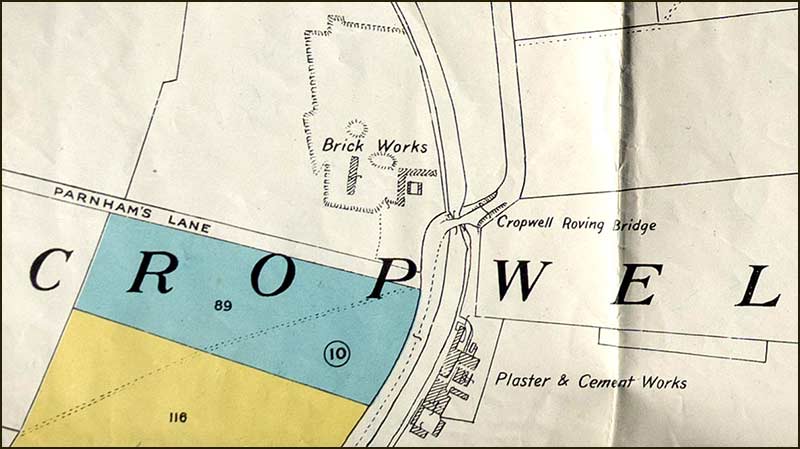

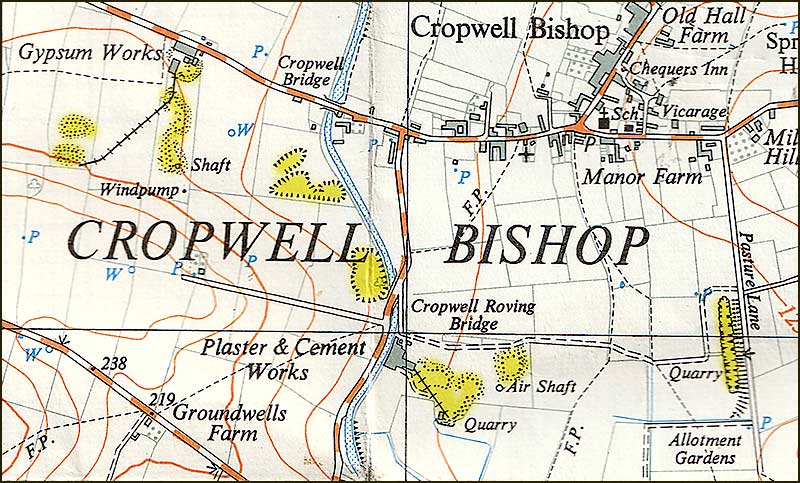

By referring to old maps, we can see how much the route of the road changed following the demolition of the bridge.

The path of this stretch of old road seems little different to how it must have been in 1930. It rises towards the road, just as it would have done when the bridge was there. (2020)

Skylark Hill

About 30m south of Bridge 22, there is gap in the hedge on the west side of the road. It is the entrance to a path that goes up the hill alongside the road.

Follow it for 10m, or so, and try looking through the hedge on the right. With luck, you will see a hill on the horizon: in winter you may be able to see a houses on it. The hill is Skylark Hill.

The houses can be more easily seen from other points.

The access road to these houses is on Colston Road — but it wasn’t always so. Originally, the road to Skylark Hill was from Kinoulton Road — just about where you are standing.

At the time of the Enclosure Act in 1804, this road was constructed to allow access to fields that were not next to a public road.

Such roads were very common when fields were smaller and more numerous. Some were given the name, Occupation Road, meaning, a road needed by people to get to their occupation (ie. their work).

This particular road was called Thorpe-in-Gate, meaning, ‘entrance to’.

In 1851, cottages were built on Skylark Hill and were known as “Hills Houses”. Later, a man named Parnham lived there, and so the roadway became known as Parnham’s Lane — and it continued to be called that until the 1970s.

Once it was decided to dig an open cast gypsum mine west of Kinoulton Road (covered later in this street story), it became necessary to create a new road to Skylark Hill. This new road joins up Skylark Hill to Colston Road and it is called, ‘Skylark Hill’.

It is understood the occupants of the houses were compensated with offers of extra land around their homes.

Gypsum

These days, we think of Cropwell Bishop as a quiet place, where agricultural products and cheese are the main industrial outputs. A century ago, it was a very different place.

Men were digging out gypsum in mines, clay was being dug up and made into bricks in the brickyards here, mills were grinding the gypsum and, all the time, barges were travelling between here and Nottingham.

Gypsum has been part of Cropwell Bishop for centuries – even before its name had been coined. Yet, it is a relatively rare mineral: even today, there are only 6 gypsum mines in the UK, and they are all within 30 miles of Cropwell Bishop.

Cropwell Mill and the Heaselden Works

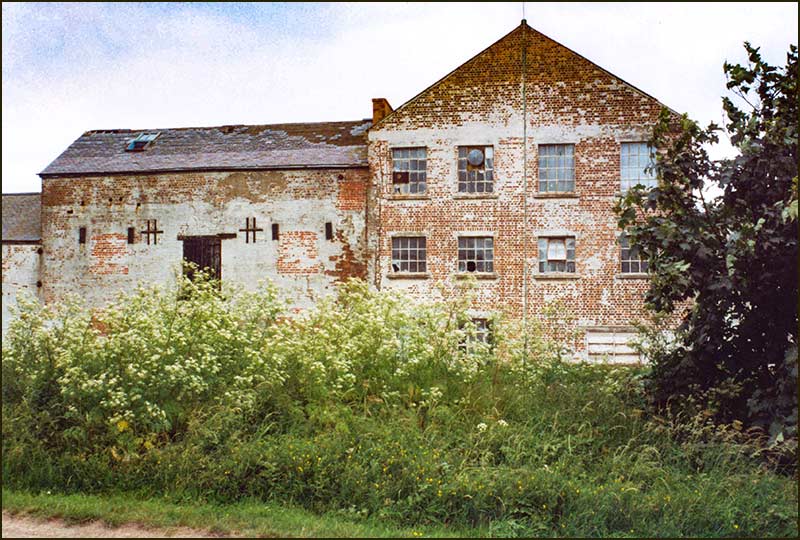

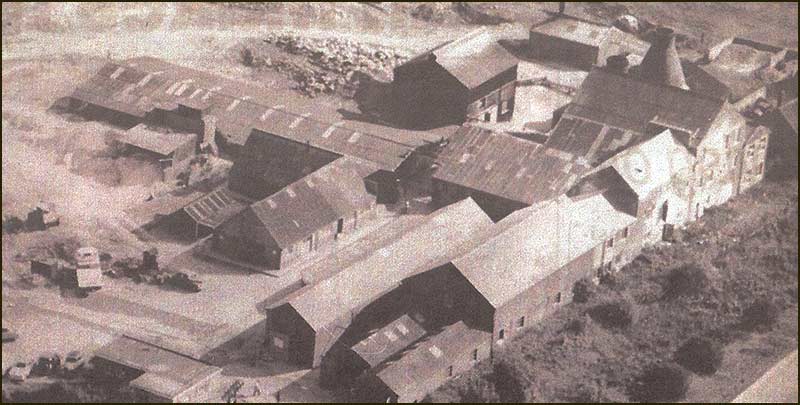

The fine looking 'Old Mill', that stands proudly on the west bank of the Grantham Canal was once the focus of the gypsum business in Cropwell Bishop. Then, it was called 'Cropwell Mill'.

It was the place where lumps of gypsum were brought from the mines and quarries; the place where they could be heated in a kiln to remove water; and the place where they were ground to a powder between steam-driven grinding stones.

And it was where barges would line up alongside the wharf to be loaded with the bagged gypsum which they would then take to Nottingham.

And it would continue like this for over 50 years until the Grantham Canal was abandoned. Even then, it would carry on with lorries doing the transporting for another 50 years.

So how did this all come about?

Lumps of white, calcium sulfate hydrate (gypsum) have always littered the fields around Cropwell Bishop; they still do.

It was long known that these rocks could be heated, and then ground into a powder which could be mixed with water to make plaster.

As long ago as 1832, it was a profitable business and Cropwell Bishop farmer, George Shelton, was listed as both a Farmer and a Plaster Merchant. He was still in the plaster trade 50 years later.

Even though there have been few gypsum mines in the UK and they have all been in the south Notts area, their seams have varied greatly in thickness and purity.

Cropwell Bishop seams have been thin, but they have been of very high purity; a great selling feature.

It was in 1878 that the plaster business really took off here. Some 408 acres of land — which included the site of the Old Mill, was offered for sale with the promise of "having valuable beds of gypsum".

The land was purchased and the "Cropwell Bishop Brick, Cement and Plaster Company" was formed.

Within 2 years, an inclined open quarry had been excavated and gypsum seams suitable for tunnelling had been located. This would have been the signal to go ahead with the building of Cropwell Mill and start production. That was in 1880.

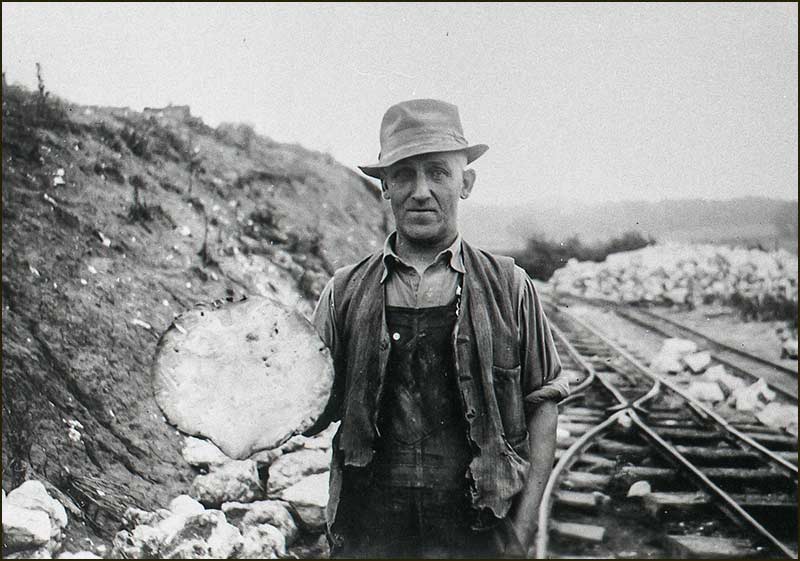

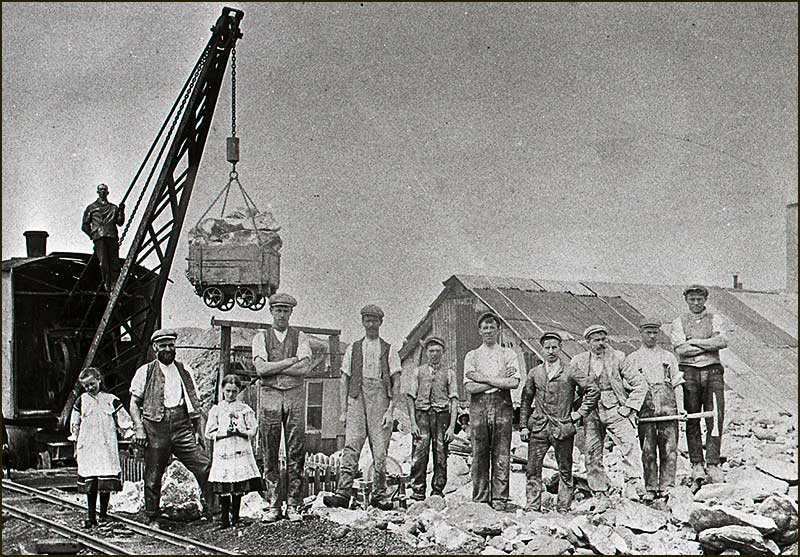

Men would work in gangs of 3. A gypsum seam 30cm thick was considered good, and they would work in tunnels just 1.4m high.

As the workings progressed, additional shafts would be sunk, typically 10m deep. Tubs would be used to lift up the gypsum — and to transport the miners up and down.

By creating new shafts, the slow and hard work of manually moving rocks along underground tracks, was reduced.

It resulted in a large number of deep shafts in the fields around — a hazard for both animals and humans.

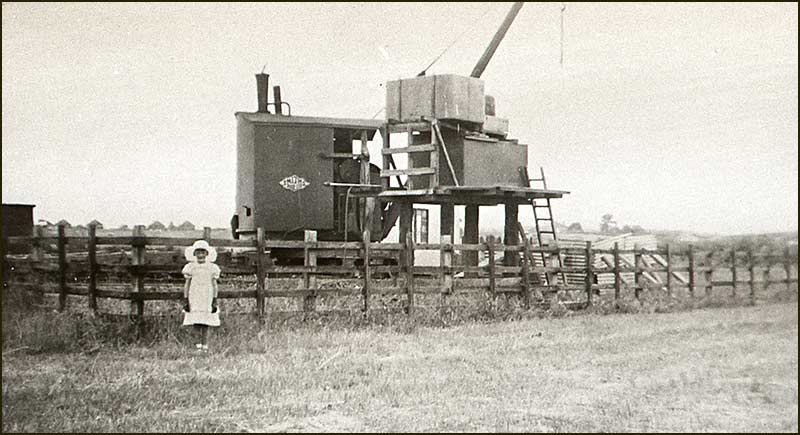

After the lumps of gypsum had been lifted to the surface, they were loaded onto railway trucks and taken to the Mill.

Once there, they were cleaned in the "dressing shed" using hand chisels or, decades later, air chisels.

What happened next depended on its final use. If it was simply to be added to soil to reduce its acidity, or as a fire preventative in a coal mine, it would be immediately ground into a powder.

On the other hand, if it was to be used to make Plaster of Paris (for model making) or plaster casts in hospitals, it would first be broken into smaller lumps, heated in a kiln to expel its water content, before finally being ground into a powder.

It all depended on sales demand.

The mill stones were like those in a windmill used to grind corn — but they were driven by steam, not wind.

The gypsum was then transported by canal barges to Nottingham – a 10 hour journey, before being forwarded by train to customers.

Records show that in 1905 the mine and Cropwell Mill were being operated by a new company, "The Phillips Company (Notts) Ltd". Then, in 1909, the Mine and Mill closed down.

We don't know why, but maybe it had something to do with a wealthy man named Sam Heaselden, who had come to live in Cropwell Bishop about 8 years earlier.

He had had a house built, Ebenezer house on Church Street, and moved in with his family. He then bought land around the village — including land south of where the Creamery Storage Unit now stands on Nottingham Road.

He sunk a shaft at a spot between Skylark Hill and where the Creamery’s Storage Building now stands. When the shaft was about 25m deep, he found what he was hoping for: gypsum of high purity.

Under these fields were men mining gypsum.

Gangs of miners would tunnel into the seams of gypsum to remove it – using explosives when necessary. It was hard work and dangerous: men died underground.

He built the "Heaselden Works" (just where the Creamery Storage Unit now stands), and started processing gypsum in similar way to the Cropwell Mill on Kinoulton Road — except he did not have a kiln to make anhydrous gypsum.

They are standing near the shaft that was behind the Heaselden Works on Nottingham Road.

The crane in the picture is shown lifting a load of gypsum from the bottom of the shaft.

And all this was in 1909 — the year that the Phillips Company stopped production at Cropwell Mill. Was this a coincidence, or was Phillips unable to compete profitably?

Heaselden also used canal barges to move his gypsum, but he loaded them at a wharf near to his Works — beside Town End Canal Bridge (where Nottingham Road Crosses the Canal).

The basin on the north side of Town End Bridge was wide enough for barges to turn around — essential for return trips.

The gypsum from the Heaselden Mine was of high quality – as good as any in the country, and much of it was used in paper making. Other uses included; bleaching, brewing, and toothpaste.

Within 15 years, output was over 150 tons a week — enough to send a full barge to Nottingham every day of the week.

Even the 'waste' clay found ready buyers. It was used as a top dressing on cricket pitches and tennis courts.

Meanwhile, the Cropwell Mill on Kinoulton Road, had been taken over by "Cropwell Gypsum Mines Company Ltd." and started production again.

Just 2 years later, in 1913, it was itself taken over by "The Gotham Company Ltd".

About 30 years later, it became part of the British Plaster Board Company which had its headquarters at East Leake.

Local businessman, Chris Allsop, had been contracted to use his cranes to clear the buildings of old machinery, but then realised that the site offered a great development opportunity — so he bought it.

He converted the buildings it into industrial units and offices and then added further buildings.

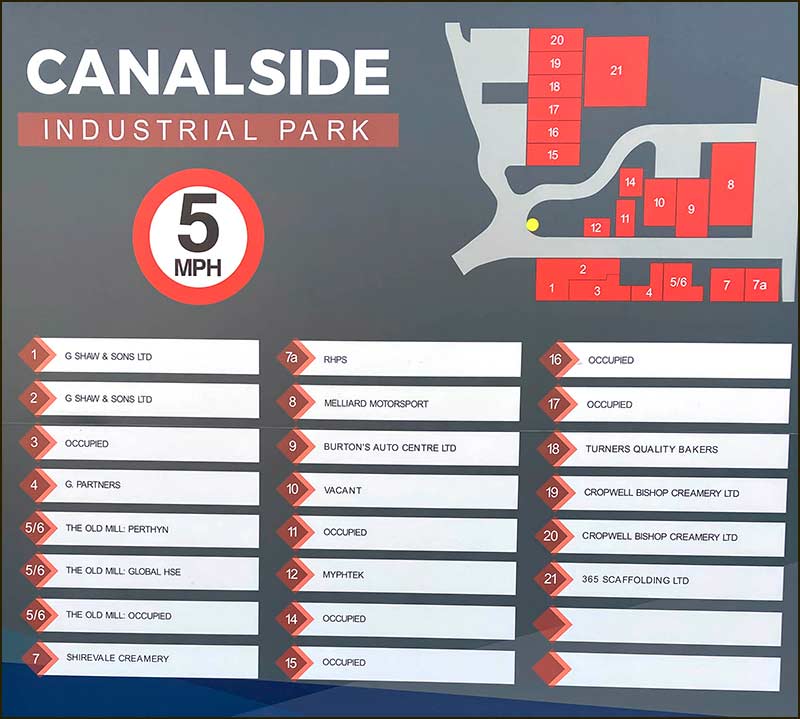

Now the 'Canalside Industrial Park' is home to a multitude of small and medium businesses. They can service your car, install you a heat pump, make outdoor signs, supply medical equipment, etc.

This time around, the canal is not there to transport your goods, just a very pleasant feature. A nice place to work.

The Last Gypsum Mine in Cropwell Bishop

It was in the 1980s that the next stage of gypsum mining in Cropwell Bishop occurred — and it would be the final stage.

No shafts or tunnels, just one giant hole in the ground: an open cast gypsum mine. It was dug in the fields west of Kinoulton Road.

When mining ended in the quarry, there were suggestions that this giant hole could be used for the dumping of a great deal of rubbish.

Unsurprisingly, this idea did not go down well with the people of Cropwell Bishop. Following a protest meeting at the Memorial Hall — which was packed, the idea was eventually dropped.

In 1999, on one evening in August, a live theatrical production of ‘Quatermass and the Pit’ was staged outdoors in this gypsum quarry. Fortunately, the weather was dry.

Quatermass and the Pit was first released as a BBC television serial in 1958. It was a science fiction horror serial which had children hiding behind the settee, too scared to see what happened next (or was that just me?).

It was in black and white and, if you saw it today, you would laugh. But in 1958 it was terrifying: rather less so in 1997.

It is now over 20 years since gypsum was last mined in Cropwell Bishop.

Up the Hill to Colston Road

Kinoulton Road drops down after the Old Mill before rising to up to Colston Road crossroads. On the left as you go up the hill, live the 5 remaining residents of Kinoulton Road.

Near the foot of the hill, the canal is very near, and also very wide. This wide section of the canal was called ‘Willow Holt’ and it is where barges were able to turn around.

The first 4 houses are built on the site of older houses built in the 1930s. The last one is much newer and is built on land that was once part of the surrounding paddock.

Tony Jarrow

Note:

Thanks to Anne Terzza, Pam Barlow, Tony Carter and Lance Thorpe for their help with this article.